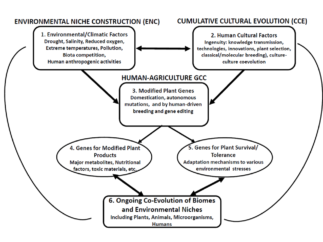

In our recent paper, “Understanding agriculture within the frameworks of cumulative cultural evolution, gene-culture coevolution and cultural niche construction” (Human Ecology 47:483–497), we apply the framework and concepts of Gene-Culture Coevolution (GCC), Niche Construction (NC) and Cumulative Cultural Evolution (CCE) to agriculture. All three concepts were originally conceived with respect to human culture and human genes, and later on also with animal genes (mainly domesticated animals). However, to the best of our knowledge, ours is the first full discussion of how plant genes coevolve with human cultural practice.

Organism-Constructed Environments are Different

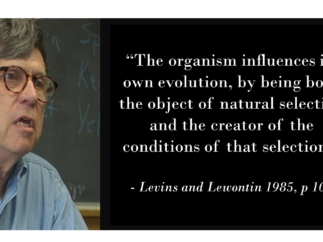

I am very happy that the article Niche construction affects the variability and strength of natural selection, which I co-authored with Andrew Clark, Dominik Deffner, John Odling-Smee, & John Endler, has just been published in The American Naturalist. I’ve argued for a long time that niche construction – the modification of environments by organisms – is an evolutionary process, but the idea remains contentious. I’d like to think that this paper is potentially significant, because it helps to make the case that the environmental conditions manufactured and modified by organisms differ in important respects from non-constructed environments, which results in different responses to selection.

Does Inheritance Need a Rethink? Conceptual Tools to Extend Inheritance beyond the DNA

Inheritance is an essential component of evolutionary processes. Without inheritance, evolution by natural selection cannot lead to the accumulation of complex, adaptive traits. But what can be inherited, and how?

The Hot Spring Hypothesis for the Origin of Life and the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis

Niche construction, feedback cascades, and how food is produced in Polynesia

Few cultural practices are more fundamentally tied to the environment than agriculture. Because of this, archaeological explanations for the development of food production systems throughout the world have privileged the concept of adaptation. Adaptation in this context has referred to the functional role played by agricultural techniques in an environmental context, for instance the development of drainage ditching in marshlands, though the definition of adaptation is rarely made explicit. Given this particular usage of the term adaptation, the archaeological investigation of “adaptation” has largely centred around the role of the external environment, both physically and culturally defined. Frequently, explanatory narratives evoke a variety of catalysts that range from climate change to socio-political demands within particular environmental settings. While these factors have no doubt affected the evolutionary rate and trajectory of food production throughout the world, understanding the actual manifestation of agricultural systems at any given time requires evaluating the evolution of selective pressures resulting from feedback loops linking human cultural practice and ecological change.

Maternally transmitted dung beetle microbiota are species-specific, and impact host development across generations

Much of evolutionary biology is motivated by one basic question: what determines biological diversity? Traditional explanations emphasize the role of natural selection acting on variation among the individuals that make up a population, sorting them into fit and less fit versions, thereby creating adaptation and diversification across generations. However, recent advances in the study of host-associated microbes has complicated this understanding. The microbial symbionts now known to reside in and on virtually all eukaryotic organisms exert a vast array of influences on their hosts. Processes as diverse as early embryonic development, gut formation, digestion, and the regulation of some behaviors have now been shown to be influenced by the microbiota (see a previous blog post). Though this line of evidence is exciting, the degree to which microbes and hosts may influence each other’s evolution remains largely unexplored.

Darwin 1.0: Is the EES playing catch-up?

A consequence of the gene-centric view of evolution we call the Modern Synthesis (MS) is to foster a severe constriction in scientists’ understandings of Darwin. Despite Darwin’s original treatment of evolution being enormously rich, he becomes the purveyor of just one dangerous idea: evolution by natural selection – the idea which, when modified by the post-Darwinian discoveries of Mendelian and population genetics, underpins the MS. Hence we find Richard Dawkins catching the gist of a hundred biology textbooks by claiming both that ‘the selfish gene theory is Darwin’s theory expressed in a way that Darwin did not choose’ [1], and, that while Darwin believed in the ‘Lamarckian’ principle that acquired characters were heritable, this belief ‘was not a part of his theory of evolution’ [2]. Only in such an intellectual world, a world still sustained by MS assumptions, could the MS be said to capture the ‘central tenets’ of Darwin’s work [3].

Is social transmission a forgotten force in coevolution?

During the last decade it has become impossible to ignore that social transmission of information occurs across the animal kingdom:1 humans and non-human animals alike learn by observing others. An explosion of studies demonstrate that species as diverse as Drosophila fruit flies to humpback whales either copy the behavior of others, or use it to alter their behavioral responses at a later date (social learning). If female fruit flies observe males attracting other females, any other males that share similar markings also become sexier,2 for example, while new methods for catching fish spread rapidly among humpback whale populations, mapping on to social networks of interacting individuals.3 Interestingly, social transmission does not seem to be a hallmark of socially-complex species.4 In fact, even solitary fish species are just as likely to use social information as those that live in shoals.5

The variational ratchet: Intuiting the variational approach to niche construction

The principle of evolution by natural selection provides a solid conceptual tool to understand adaptive design. It operates like a ratchet, to retain and build upon functional variation. Pull down, ‘click’! Variation. Hold tight, lock it! Retention and differential fitness. Push up! Inheritance, and ratchet your way up towards peaks in the adaptive landscape. As this process is repeated over phylogenetic time, the organism-environment complementarity will tend to get tighter and tighter, often leading to enhancements in the properties of adaptations.

Pleiotropy allows the evolutionary maintenance of positive niche construction in the face of free-riders

In our paper published recently in American Naturalist, we used mathematical models to help us understand how positive niche construction can be maintained. Many animals, plants and other organisms engage in niche construction, that is, they modify the environment and the subsequent selective pressures to which they are exposed. Positive niche construction occurs when organisms modify the environment to their advantage; for example, beavers create dams to provide shelter and other benefits. So-called free-riders can emerge who don’t contribute to the costly niche construction but still benefit from the niche-constructing activities of others. This raises an evolutionary problem of how positive niche construction can emerge and be maintained if it is constantly challenged by free-riders.