Could Planet of the Apes actually happen?

31 July 2017

Following release of the blockbuster movie, biologist Kevin Laland asks ‘Why not?’

This week many of us will watch an army of retrovirus-modified apes wage brutal war against humanity. Unquestionably, chimpanzees on horseback, machine-gun-wielding gorillas and tutoring orangutans make spectacular theatre, but could it happen in reality? As people around the globe flock to revel in the latest CGI-enhanced dystopian fantasy, it is interesting to ask could Planet of the Apes actually happen?

In Pierre Boulle’s original 1963 novel, space traveler Ulysse Mérou becomes trapped on a terrifying planet in which gorillas, orangutans, and chimpanzees have seized control, having acquired human language, culture, and technology by imitating their former masters. Cast out of their homes, humans degenerated into brutal and unsophisticated beasts. Later movie and television adaptations attributed the enhanced intellectual capabilities of ‘evolved apes’ to a retrovirus Simian Flu pandemic, and changed the setting to a post-war apocalyptic wasteland.

Much of the sinister realism of Boulle’s novel stems from the author’s impressive knowledge of research into animal behavior, and attention to scientific detail is equally manifest in movie adaptations. Yet, at least here on planet Earth, other apes could not actually acquire major features of human culture solely through imitation, nor could sleeping apes be rendered highly intelligent overnight through breathing in a brain-enhancing drug. Infections can lead to behavioral changes (e.g. increased aggression in rabies sufferers) but they can’t ‘give’ a species language. Complex culture requires an underlying biological capability fashioned through long periods of evolution. Yet Boulle was prophetic in his suggestion that imitation played a central role in emergence of culture.

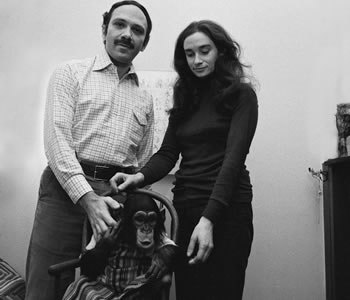

A romance exists around the notion that animals, such as chimpanzees or dolphins, covertly harbor complex communication systems unfathomed by humans. We rather like the idea that ‘arrogant’ scientists have prematurely concluded that other animals can’t talk after failing to decode their calls. Sadly, animal communication has been subject to intense scientific investigation for over a century with few hints of such complexity. Outside the movies, chimpanzee vocal control and physiology is incapable of speech production. This much was established in the 1940s by researchers who raised a chimpanzee called Viki in their home. Disappointingly, Viki learned just four words—“mama,” “papa,” “cup,” and “up”. That was at least more successful than an earlier attempt to rear a chimpanzee and child together: the exercise had to be abandoned with the chimpanzee failing to learn a single word, but the child imitating chimpanzee sounds!

Much excitement was generated by studies teaching apes sign language, yet claims that apes had produced language did not stand up to close scrutiny – a point on which virtually all linguists concurred. The animals could learn the meaning of signs, but failed to acquire the rules of grammar. Revealingly, ‘talking-ape’ utterances proved devastatingly egocentric. Given the means to talk through signing, apes say “Gimme food” or other expressions of its desires. The longest recorded statement of any ‘talking ape’ – produced by a chimpanzee called Nim Chimpsky – was “Give orange me give eat orange me eat orange give me eat orange give me you.” Outside of the movies, chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas make poor conversationalists.

By contrast, months after uttering their first words, two-year-old children produce complex sentences, comprising verbs, nouns, prepositions, and determiners in the correct grammatical relations and on diverse topics. That is because humans have minds uniquely fashioned by evolution to comprehend and produce language. Many scholars believe that language began with the creation and use of meaningful signs, and that being immersed in this symbol-rich world generated evolutionary feedback favoring neural structures capable of manipulating and using symbols efficiently. The syntax manifest in human language is possible only because of a long history of symbolic manipulation in protolanguage, which elicited a reorganization of the human brain. Genes and culture co-evolved.

The same holds for warfare. War is much more than scaled-up aggression: it requires extensive cooperation regulated by complex institutions specifying strict behavioral codes. To wage war, individuals must coordinate with allies in organized and often distinctive roles. Research suggests that this type of cooperation could not evolve in a species that lacked complex culture: stabilizing forces such as institutionalized punishment (e.g., by a police force) or socially sanctioned retaliation (e.g., beating of deserters during warfare) are required for such cooperative norms to persist. Most norms are far from obvious, and youngsters must be taught both the nature of the norms and the need to conform to them. Other apes are proficient imitators, but there is little compelling evidence that they actively teach, and correspondingly their cooperation largely entails helping relatives. The scale of human cooperation, which involves huge numbers of unrelated individuals working together, is unprecedented in large part because it is uniquely built upon learned and socially transmitted norms. These norms are the glue that ties individuals together into cooperating teams.

We now know that our ancestors’ cultural activities generated natural selection on the human brain, which in turn further enhanced cultural capabilities in recurring cycles. There is extensive evidence for this kind of evolutionary feedback. For instance, milk-drinking began with early Neolithic humans, who were consequently exposed to strong selection favoring genes that break down the energy-rich sugar lactose, which is why many of us with pastoralist ancestors are lactose tolerant. Gene–culture coevolution has shaped human biology.

No wonder that Boulle emphasized imitation. Humans are descended from a long line of inveterate imitators. Through copying the fear responses of other individuals, our ancestors learned to identity predators and circumvent dangers. This helped to shape the empathy and emotional contagion that makes the movie a heartfelt experience. In the absence of these abilities, we would all watch movies like sociopaths, equally unmoved by the Psycho shower scene or Rhett Butler and Scarlett O’Hara’s kiss. By copying, our forebears learned how to make digging tools, spears, and fish hooks; how to butcher carcasses or build fires. These, and countless others skills, were what shaped the polished, imitative capabilities of our lineage, leaving it supremely adapted to translate visual information about the movements of others’ bodies into matching action from their own muscles, tendons, and joints. Eons later, today’s movie stars can direct this aptitude to imitating the movements of other primates, with a precision no other species could match. Human culture is not something that another species can easily pick up – but reliant on evolved propensities millennia in the making. There will be no inter-primate war on Earth until such a time as other species have undertaken a prolonged evolutionary journey – one that the only real-life warmongering ape currently appears hell-bent on preventing.

This post was originally published on Adventures in Poor Taste, 13 July 2017