A group of biologists, philosophers and historians of science recently gathered at Ruhr University Bochum (RUB) for the 7th Workshop on History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences organized by Jan Baedke and Christina Brandt, entitled “The Extended Evolutionary Synthesis: Philosophical and Historical Dimensions” (21-22 March, 2019). This multidisciplinary community of scholars was brought together to reflect on past and present conceptual, explanatory, methodological, and sociological challenges that developmentally-oriented views in evolutionary biology face. The Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES) was used as a stepping stone for many of these discussions; however, also other important philosophical and historical topics were addressed that ‘extend’ beyond this conceptual framework.

From plasticity to diversity: accommodation of ancestral plasticity results in divergent developmental rates in spadefoot toads

"A plausible argument could be made that evolution is the control of development by ecology" Van Valen, 1973

The evolution of anti-teaching

In 1921 a British tit was observed opening a milk-bottle to eat the cream inside, and over the next 26 years this unique innovation spread to over 30 different sites. As just one example out of hundreds, this shows how animal populations contain a mixture of innovation and learning, with novel behaviors discovered, developed and spread through social learning. The question is, if these behaviors are advantageous to learn, are they ever adaptive enough for a demonstrator to teach?

Workshop report: Developmental Biases in Evolution

"Developmental bias is a manifestation of a much more fundamental principle, and is the norm rather than the exception", according to one scientist. "Developmental bias is a misleading term and we should get rid of it", according to another. Both were in the same room, at the same time. So what is developmental bias, what role does it play in evolution, and why do we even care? These questions were the focus of an interesting and spirited workshop, the third in a series of EES project meetings, held recently at the Santa Fe Institute. As with the first meeting, I was able to sit in on this workshop, like a fly on the wall, and listen to the presentations, arguments, and debates. Here's what I learned...

Talking Evolution workshop report

In the last week of September, the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Plön, Germany, hosted a workshop entitled Talking Evolution. Key topics discussed were niche construction, phenotypic plasticity, developmental bias, and extra-genetic inheritance. The workshop was organized by Noémie Erin, Alice Feurtey, Vandana Venkateswaran and Dominik Schmid, four early career researchers, and Maren Lehmann, the workshop coordinator at the MPI. Katrina Falkenberg interviewed the organizers about the workshop, how it came about and their highlights from the three days of talks and discussions.

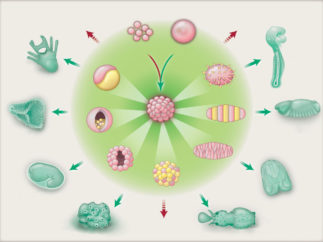

Physical mechanisms of development and evolution: An interview with Stuart Newman

Stuart Newman is a Professor of Cell Biology and Anatomy at the New York Medical College in Valhalla, New York. He is a prominent evolutionary developmental biologist, well known for his pioneering work on vertebrate limb development and the role of physical mechanisms in development and morphological evolution. Katrina Falkenberg is the science communication and outreach officer for the EES research program. She interviewed Stuart about physical mechanisms of development and their importance for understanding evolution.

Ancestral plasticity paves the way for evolutionary novelty in spadefoot toads

The question, “Where do new traits come from?” has long puzzled evolutionary biologists. New traits are often assumed to arise exclusively from genetic changes – including, but not limited to, mutations in regulatory sequences or gene bodies, inversions, and gene (or genome) duplications. Mary Jane West-Eberhard formalized a hypothesis in which the evolution of novelty can begin with new mutations or with environmental perturbation in her 2003 book Developmental Plasticity and Evolution. Indeed, the interchangeability of mutation and environment on phenotype production has a long history (e.g. Drosophila phenocopies). Despite West-Eberhard’s emphasis on adaptive evolution starting with mutation or environment, the aspect of her hypothesis that has really taken off is the latter – when trait origin occurs because of environmental perturbation of development. Indeed, a growing number of researchers have begun asking if environmentally initiated phenotypic change (i.e., phenotypic plasticity) might initiate novelty.

The unlikely but fruitful waltz of a curious couple: Phenotypic plasticity and learning theory

When the Modern Synthesis was put together in the early decades of the twentieth century, natural selection became the obvious focus of evolutionary thought. Although this focus has increased our understanding of biological evolution by orders of magnitude, it tells us little about how phenotypic variation is produced. Variation – the third evolutionary pillar envisioned by Darwin (the other two being selection and heredity) – is typically taken for granted, and assumed to follow from the random, isotropic, and unbiased genetic changes that arise by mutation.1

Extended Heredity: An interview with Russell Bonduriansky and Troy Day

Extended Heredity: A New Understanding of Inheritance and Evolution is a fantastic new book by Russell Bonduriansky and Troy Day about the role of nongenetic inheritance in evolution. There are many similarities between the views presented in the book and the extended evolutionary synthesis but there are also differences. Kevin Laland identified some of these in his book review for Science and we wanted to take a deeper dive into some of the key issues. Katrina Falkenberg asked Russell and Troy some questions about the evolutionary significance of nongenetic inheritance, and asked Kevin to elaborate on some points he makes in his review.